UVA Wise Students Harvest the History of the Region

Students from University of Virginia’s College at Wise (UVA Wise) recently worked together to harvest the history of mine rescuers from the Westmoreland Coal Company’s Stonega Division. The project was a collaborative effort between the Center for Appalachian Studies and students in the College’s Introduction to Public History course.

The project honors a major industry of the region the College calls home. Students participating preserved the past by scanning in newspaper articles and old photographs, taking photographs of artifacts, and becoming fully immersed in local history.

From 1976 to 1992, Westmoreland Coal Company’s Stonega Division mine rescue teams entered five different exploded mines in hopes of rescuing trapped coal miners, which were unfortunately unsuccessful, while also considering the dangerous conditions of entering the exploded mines. Those in attendance worked the two Scotia explosions in 1976 (Matt Smith, Gerald Tate, J. R. Kimberlin, Allen Wolfe, and Bill Person), the 1977 P&P explosion in St. Charles, Virginia (Smith, Tate, Kimberlin, and Wolfe), the 1980 Ferrell explosion in West Virginia (Tate, Cotton Gardner, Kimberlin, Person, and Wolfe), and the 1992 Southmountain blast near Norton (Hughie Carter, Tate, and Gary Whisman), said Brian McKnight, UVA Wise history professor and co-founder of the College’s Center for Appalachian Studies.

History fanatic and UVA Wise sophomore Lamore Tucker from Big Stone Gap, Va., stood behind the camera, thrilled to take part in collecting their histories.

“One of my favorite things about history is being taught by others. The personal connections that can come out of telling stories is something I really enjoy. Having these people here, revealing specific parts of their lives first-hand is something you can’t get out of a textbook,” said Tucker.

Mine rescuers reminisced and shared stories of their work in a convivial atmosphere.

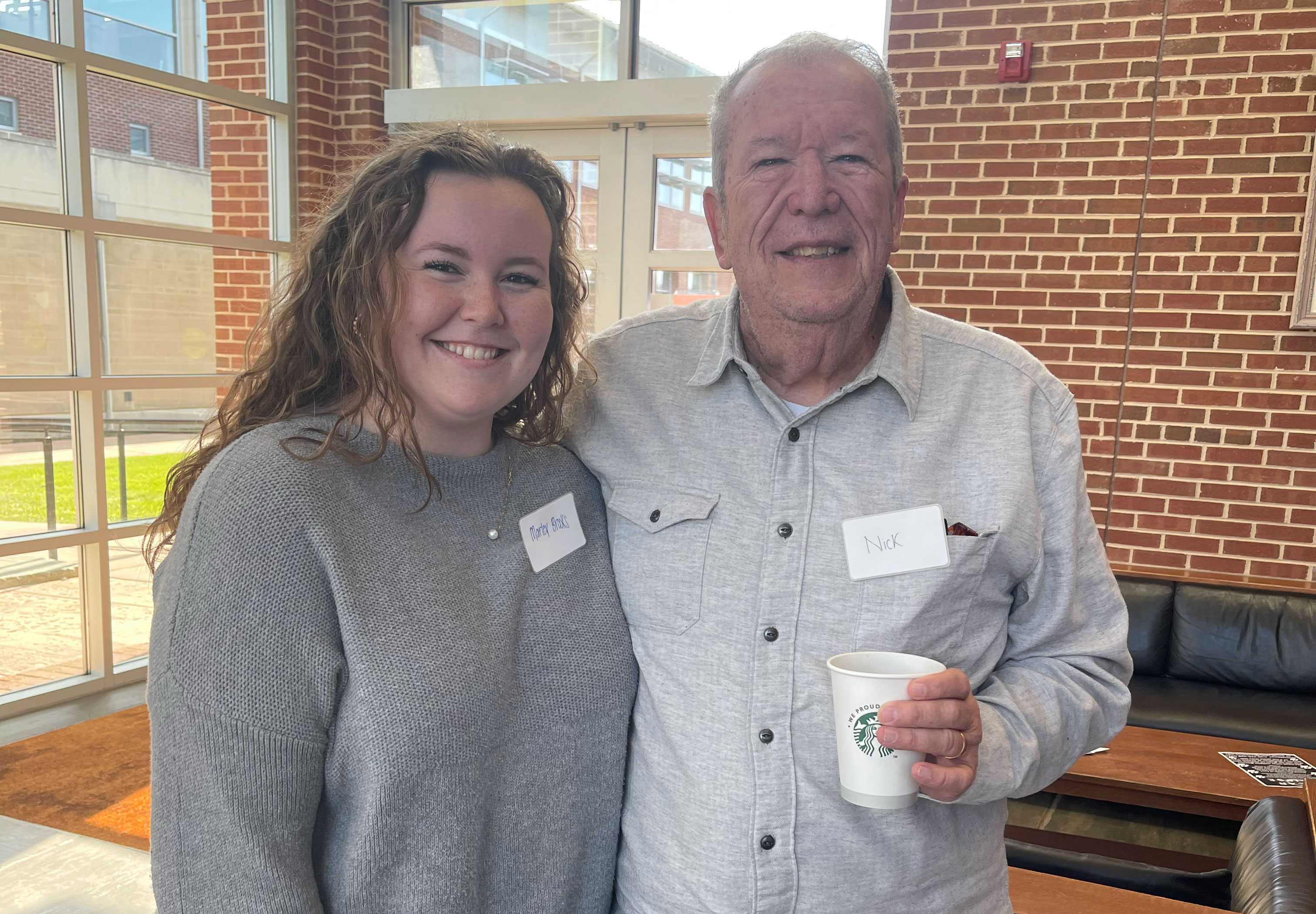

UVA Wise sophomore Marley Brooks, a history major and Appalachian Studies intern from Gate City, Va., had a personal connection to the project unlike any of her peers. One of the men in attendance was her grandfather, Rev. Nick Brewer, who holds a doctorate in theology, and is also a 1972 graduate of then-Clinch Valley College. Brewer was not part of the Mine Rescue program, but he served as a MSHA mine inspector at the time and worked closely with the men on the teams, McKnight said.

Brooks and Brewer sat down to discuss the importance of preserving public history. Brewer, who is a third-generation coal miner, was a part of the Scotia Mine Disaster of 1976, which took place in Letcher County, Ky., where he served as a mine inspector that helped restore the mine after the explosion while also assisting with victim recovery.

“It means the world to me to have my grandfather come out to tell his story. He has been telling me many of these stories throughout my life, and it's important to have them known,” said Brooks. “The work that he did, and many other miners and mine rescuers did, was very important to this community, and I am so happy that they have this outlet to tell their stories.”

Associate Professor of History Jinny Turman, who teaches the course, emphasized the importance of providing her students with experiential learning opportunities.

“For the students interested in entering the field of public history, it is very useful to have experiences such as this under their belt. It also helps them become connected and grounded within their communities a little bit more,” said Turman. “It’s not just about job training, it’s about teaching them to learn to listen to the people around them in a way that makes them want to share their histories.”

Mine rescue was a way that the mining industry and the UMWA could come together for a common cause. Although their relationship was often adversarial, both sides agreed that safety was important and seemed capable of working together when faced with a crisis, McKnight said.

Many of these men worked four of five explosions and one worked all five, including Southmountain in 1992. For Gerald Tate, who worked all five, he helped locate forty-three dead miners throughout the course of his service, McKnight said.