UVA Wise Undergrad Students Publish Ground-Breaking Freshwater Mussels Research in Prestigious Journal

Four undergraduate students at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise (UVA Wise) took a novel approach using applied DNA techniques to study the dietary preferences of freshwater mussels in the Clinch River, resulting in significant new findings published recently in a major journal.

Nature’s “Scientific Reports” published the research article, “Freshwater mussels prefer a diet of stramenopiles and fungi over bacteria,” in late May.

UVA Wise students Tina Etoll and Rachael Sproles and then-students, now graduates, Isabella Maggard and Kayla Deel were the article’s lead authors along with Tim Lane, director of mussel recovery at the state’s Aquatic Wildlife Conservation Center and Bruce Cahoon, UVA Wise Buchanan Endowed Chair of Biology, who oversaw and guided the experiments aimed at freshwater mussel conservation.

The research shows that one species of freshwater mussel (Pheasantshell, Ortmanniana pectorosa), which has been suffering severe declines since 2016, has a different diet from the other mussels studied—which could offer a clue as to why it has been dying.

So far, previous attempts to find a disease, virus or bacteria to explain these die-offs have been short of conclusive.

The other mussel species studied are consuming two specific families of fungal spores from the river, the project shows. One of these fungi cause agricultural plant diseases and the other causes herpetological die-offs like salamanders. This demonstrates the importance of maintaining healthy mussel beds in the rivers as it shows the mussels can help reduce agricultural pests as well as contribute to the overall ecology of the Clinch River, Cahoon said.

The projects also dispelled the belief that these mussels eat bacteria and revealed most species prefer algae and fungi, yet some may consume bacteria as a last food resort. This work also demonstrated that mussels have dietary preferences and do not simply eat anything that they can filter from the water.

The results are relevant to the Southwest Virginia community and environment because they provide a better understanding of the dietary needs of freshwater mussels, which is crucial for conservation efforts. Knowing the preferred diet of freshwater mussels can be used to manage mussel health and support propagation efforts, Maggard said.

Typically, studies that get accepted in journals like Nature’s “Scientific Reports” are conducted by R-1 universities or research institutes, Cahoon said.

“For a group of four undergrads to have accomplished a study that's significant enough to go into one of the Nature journals is rare,” he said. “I believe this will become a landmark study as it demonstrates a basic element of their biology, what they like to eat. We were surprised to learn how little was known about this basic element of mussel biology.”

A Barry Goldwater scholar, Maggard who won the UVA Wise Chancellor’s Medal for her work on the project, said she was proud of having played an active role from start to finish. She helped propose the research idea, helped conduct both sets of experiments, analyzed the data and contributed to writing the manuscript.

“Most people don’t have the opportunity to be a lead author until well into their graduate studies at a large research university. As lead author from a primarily undergraduate and small, liberal arts school, this is a huge accomplishment that would not have been possible without having access to opportunities,” said Maggard, who is pursuing a doctorate in microbiology this fall at the University of Tennessee. “This publication is the result of providing talented students with research opportunities and having an outstanding mentor who developed those talents.”

Science Funding Support to Student Scholarship

When Tina Etoll first met with the other students to discuss the project she felt “way out of her league.”

A single mom and U.S. Veteran, Etoll had studied in the arts before entering the National Science Foundation Scholarships in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math scholars program at UVA Wise.

“Switching to the sciences was a huge learning curve, both personally and academically,” Etoll said.

The NSF S-STEM program is dedicated to fostering the talents of undergraduate students through various research tracks.

Two of the other students, Maggard and Deel, had worked with Cahoon before and already knew a lot about scientific experimentation as well as applied and fundamental research.

“Being a non-traditional student and Veteran means understanding that great motivations for success must be balanced with practicality. To be placed into the NSF Scholar program and to now be a published author, has removed circumstantial barriers and any perceived deficiency I may have felt toward my ability to contribute to science,” Etoll said.

In fall 2022, the four NSF S-STEM students entered an environmental genomics research track under the guidance of Cahoon.

A National Science Foundation S-STEM grant and the Buchanan Chair of Biology endowment funded the study’s research and analysis. This project was also designed and carried out by National Science Foundation S-STEM student scholars at UVA Wise.

“This is a wonderful example of how we are using grants and donor gifts to benefit not only the education of our students but the creation of new knowledge relevant to Southwest Virginia,” Cahoon said.

For Rachael Sproles, the research project was a turning point in her college career.

“After beginning the mussel research, I quickly gained three new friendships with the other girls I was working with. These friendships allowed me to grow and flourish in both social and academic viewpoints. I am beyond grateful for the friendships made and how positively my life has been impacted from these people. This experience, as a whole, has truly been the best and most rewarding experience and I have been so fortunate to be a part of it,” Sproles said.

Sproles, a first-generation student, said she never dreamed of accomplishing something like this in her first year at the College.

“Coming from a smaller high school, I always admired accomplishments similar to this, but never thought them to be attainable,” Sproles said. “However, just a few semesters later I found myself realizing that these goals were within reach.”

Freshwater Mussels, Fish Tank, Just Add Water

In his Research Methods in Environmental Genomics course, Cahoon taught the four students applied molecular genetic DNA techniques.

He said it’s similar to the forensic DNA technologies used by law enforcement. Instead of identifying people, it’s identifying other living things in the environment.

“Every living thing has DNA. The purpose of the class was to show how you can use DNA technologies to identify a wide array of living things in the environment,” Cahoon said.

When searching for a topic of research, UVA Wise students were interested in working with the nearby Clinch River renowned for its biologically diverse ecosystem.

Cahoon suggested conducting an experiment with freshwater mussels since the Clinch River has at least 46 known species of mussels. Many are unique to this region and nearly half are imperiled and dying.

“I didn't know what we might learn from it. The students immediately were interested and the four of them came up with the idea of finding what the mussels take out of the water,” Cahoon said.

For the first few weeks, students reviewed primary literature to learn what the mussels were eating and learned that there wasn't a lot known about what they eat other than they eat microbes out of the water. Mussels eat by siphoning the water through their gills, pulling it into their filter feeders and collecting food.

Freshwater mussels are a vital part of the Clinch River ecosystem because they act as ecosystem engineers—making the environment more suitable for themselves and other organisms.

The students brainstormed research questions eventually focusing on the diets of freshwater mussels using applied molecular genetic (DNA) technology that wouldn’t require sacrificing endangered or threatened mussels. They developed a simple experimental system testing the DNA of the microbes living in the water.

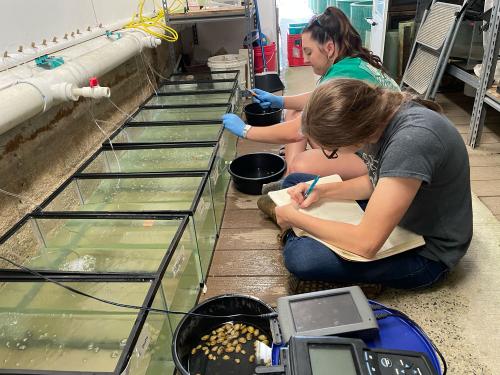

The first experiment was conducted at the College’s Oxbow Center, home of the Clinch River Ecological Education Center.

That process consisted of putting Clinch River water into a fish tank and testing what was in the water, then adding the mussels to let them eat. Then they extracted the microbial DNA from the remaining water samples and sequenced it.

“As simple as it sounds, nobody’s done that before,” Cahoon said.

The mussels were placed in 10 liters of water for 24 hours. During that time, the mussel siphoned the water multiple times over. They learned mussels like to eat certain algae and fungi, which are agricultural pathogens, and they didn’t eat the bacteria, which was formerly believed to be a part of their diet.

Since the first experiment was successful, they chose to do a second experiment in the summer of 2023. Maggard and Deel, now a biology teacher in Gate City, worked with Lane at the Aquatic Wildlife Conservation Center near Marion, Virginia, which has a state-funded mussel breeding center. It’s the first of its kind in the country and is a national leader in conservation and restoration of federally endangered mussels, Lane said.

To date, the center had produced close to 40 different mussel species and half are federally endangered species. One of its main purposes is to re-establish mussel beds in the Clinch River.

UVA Wise students used mussels bred at the center so they wouldn’t be removing endangered mussels from the Clinch River.

“We have a lot of diversity in the Clinch River but what is unique about the Clinch is that there are more imperiled species of mussels than any in the country. This is the last place that those 15 or 20 species exist in healthy numbers on Earth,” said Lane. “It’s a fragile ecosystem and it’s important that people do everything they can to preserve them for future generations,” Lane said.

Lane provided the researchers five species of non-endangered mussels: rainbow, wavy-red lampmussel, mucket, pocketbook and pheasantshell.

Some research indicates common mussels help endangered ones survive. Just like trees clean air, mussels play an important role by cleaning the water, Lane said.

For the second experiment, they repeated the first but also tested the same five species of mussels in four time periods ranging from eight hours to four days.

They wanted to determine if starving mussels would eventually eat bacteria. They learned mussels loved the algae and ate it first, then fungi. Even after starving them of their favorite foods, most still refused the bacteria except for one species of mussel.

That species, the pheasantshell, had different eating habits or dietary preferences than the others and did eat the bacteria, and it is the one experiencing high mortality in the wild.

“We don't know if we've uncovered why it's dying. But it's something we've found that distinguishes it from the others that we tested,” Cahoon said. “That's one of the reasons why it was published where it was, I think, because we've found some intriguing details.”

With the new information on diet preferences, the individuals raising mussels in this area are able to better understand what microbes to feed their juvenile mussels for optimal growth and survival rates, Sproles said.

“It shows having mussel beds benefits everybody. It's not just saying we need to save the mussels for the sake of their existence. They're part of an interconnected web of life,” Cahoon said. “Since they eat the fungi, which is a pathogen to plants and salamanders, they’re helping the rest of the ecosystem. They are removing potential pathogens from the water and eating them. It helps the ecosystem and it also helps human agriculture.”

Lane hopes to get a permit to conduct follow-up experiments on endangered mussel species in the future.

“This study has also been important for the mussels because the more people learn about them and how interesting they are, the more they care,” Lane said.